The gap between different income groups, genders, and levels of human capital accumulation has grown further, while economic inequality and in terms of non-traditional security threats has dramatically worsened. This expansion of inequality will be the largest obstacle to sustainable development, writes Kim Heungchong, President of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP). The article is published as part of the Valdai Club's Think Tank project, continuing the collaboration between Valdai and KIEP.

The global economy is rapidly recovering. After lockdown measures by nations across the world led to the most dismal performance to date in 2Q 2020, economic activity is being resumed and we are seeing a rapid turnaround in almost all sectors except for some services trade and domestic small enterprises.

According to its World Economic Outlook Update released on July 27, the IMF expects the world economy to grow by 6.0% in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022. Compared to the global economic growth rate of 2.8% in 2019, we can expect a strong pace of recovery to continue into the next year as well.

The U.S. economy, in particular, is expected to grow by 7.0% in 2021. The updated figure has been greatly marked up from previous analyses conducted in November last year, which forecasted a 3.1% growth rate for the U.S. this year. Since then, the IMF has continued to raise its outlook on the U.S. economy, up from previous forecasts of 5.1% and 6.4% annual growth. The projected growth rate for the U.S. in 2022 has also been hiked from 3.5% in April to 4.9%. Growth projections for the Eurozone and Korea in 2021 and 2022 have been revised upward as well.

The pace of strong recovery is exceeding "expectations". But does this mean we are entering an unforeseeable situation? I would argue not. The reasoning for this lies in how we should view the economic recession brought on by the global pandemic – or the Great COVID-19 Recession, as I call it. Another question is whether a hysteresis effect will appear. This effect is seen in cases where the global economy recovers from recession following a negative shock, but the effects from this shock continue to exist even after the event has been removed.

A stronger rebound than expected can of course lead to worries of inflation. There are even concerns that spread of the Delta variant will cause stagflation. These analyses are valid. However, a clearer understanding of the nature of this economic recession could lead to different judgments of the possibility of inflation.

This hardly means that the whole story is nothing but positive. The disparities between governments in their financial coping capacities and ability to supply vaccines could very likely produce a great divergence between countries. These concerns will be addressed in the following consecutive sections.

A recession without hysteresis

A proper discussion of the economic recession in 2020 caused by COVID-19 would benefit from clarification of the factors behind previous recessions and/or depressions in the history of the world economy. Broadly speaking, the Great Depression of 1930s was brought on by both demand-side factors, such as consumption falling short of production or a lack of investment compared to saving, and supply-side factors such as oversupply or overcapacity of economic capacities. Both signified a severe structural imbalance between demand and supply to an extent which could not be quickly resolved. When it comes to the economic collapse caused by the Second World War, devastating the European countries it had been fought on, such as France, there is simply no way for the economy to recover from such destruction in a short period of time. The capacity to supply has been simply crippled.

The recession caused by the two oil shocks in the 1970s was mainly caused by supply-side factors. Due to the soaring price of oil, an industrial backbone, Keynesian policies performed at the time only succeeded in producing stagflation. A more recent example would be the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. The economic shock was triggered by the subprime mortgage crisis, where an inflated level of economic optimism following the so-called Goldilocks era led to excessive investment in subprime mortgage-backed assets, and eventually to firms and banks in related sectors going bankrupt in the aftermath of a bubble burst. This led to a crisis of credit.

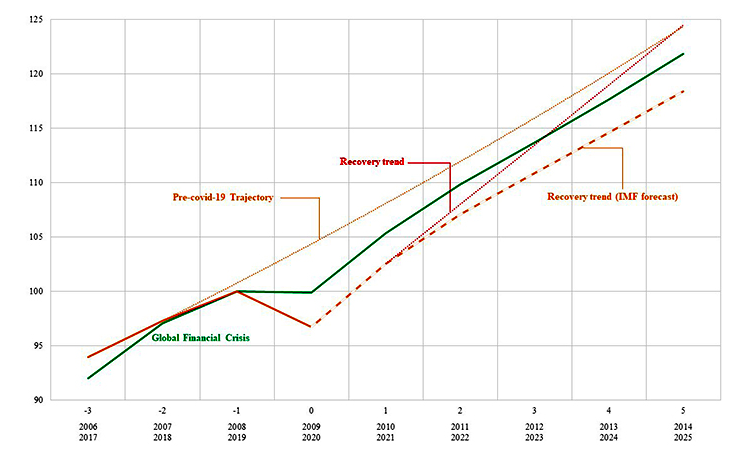

This nature of economic decline is what produces the hysteresis effect, where a negative shock leaves a permanent mark on the economy. Even after the shock has subsided and economic growth rates have recovered to pre-crisis levels, indelible scars remain in the economy and the trajectory of growth permanently diverges from the path which would have been realized without the crisis (see Figure below). In the case of the Global Financial Crisis, the area on the graph between the thin dotted line and green solid line can be seen as the permanent loss in economic growth caused by the crisis. This is a hysteresis effect.

When compared against the periodical economic crises occurring throughout history, the COVID-19 economic crisis of 2020 stands out due to its novel nature. In the absence of any serious imbalance in supply and demand, indeed any imbalance across the entire global economy or any credit crisis, the pandemic caused an exceptional situation where personal contact was prohibited and cross-border travel was limited.

The world was thrown into a situation where people were forced to shun each other, almost as if a zombie outbreak had occurred.

Demand and supply rapidly shrunk and all industries relying on personal movement were crippled. The resulting contraction in the economy has been enormous in scale, but the nature of this situation also means that normalcy can be rapidly restored once the pandemic is over. We are experiencing an economic recession highly unique in nature and virtually unprecedented.

As mentioned, it naturally follows that the unique nature of this recession caused by the global pandemic means economic recovery can proceed rapidly in the post-COVID-19 world.

This, of course, comes with a premise. Supply capacity must remain intact throughout the long periods of lockdown forced by the pandemic. Indeed, the unprecedented expansionary fiscal measures carried out by governments in advanced nations over the past year and half are aimed at maintaining this capacity to supply. An astronomical amount of funds have been poured into maintaining production facilities, production capability, and human capital. The operating losses inflicted upon businesses due to lockdown measures or lags in economic activity were simply converted into government debt. Supply capacity will be maintained in nations where this process was relatively smooth, and economic recovery will proceed at a rapid pace in post-COVID-19 conditions.

This is the line of reasoning I have continued to advance since last year. My assertion is that expansionary fiscal policies must be carried out aggressively, and that as long as these policies are maintained, the economic rebound will be more rapid than expected. This is the economic rebound we are seeing this year, which exceeds previous forecasts. The projections released in April by the IMF, on the other hand, remain closer to ordinary recovery trajectories seen in the past (see Figure).

Remaining problems

When such a rapid pace of economic recovery is coupled with powerful expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, there is a concern of inflation rising in the economy. Coming into 2021, the inflation rate in major economies has exceeded 2%, the upper limit of inflation implicitly maintained by central banks around the world for the past two decades. While many central banks are taking a dovish stance on their inflation targets and allowing rates of inflation close to or even exceeding 2%, there are worries over inflation prompted by strong recovery having a sudden and major impact that engulfs the global economy. As of yet, I do not concur with these concerns. In other words, I believe it is too early to begin normalizing the current monetary and fiscal expansion policies. The grounds for the reasoning are based on the roots of the crisis.

The current economic crisis is the result of movement restrictions imposed to prevent face-to-face transactions, and there is an inevitable time lag between recovery of demand and supply during periods of economic recovery. As such, demand will rebound quickly and strongly as deferred consumption activities and investment are resumed. On the other hand, it will take time for economies to recover their supply capacities. Time will be needed to put idle facilities back into operation and for industries to secure personnel with the proper human capital to resume their operations. This temporary mismatch between demand and supply could occur in any industry or field. Such a bottleneck problem may result in localized inflation spikes in the short term, but will be far from sustained or structural inflation. The authorities implementing policies in each nation should resist the temptation to prematurely normalize policy.

Then what is the most important problem left to resolve? This is none other than the massive expansion of inequality caused by the pandemic. The post-COVID-19 era deserves to be called the era of the great divergence. The gap between different income groups, genders, and levels of human capital accumulation has grown further, while economic inequality and in terms of non-traditional security threats has dramatically worsened. This expansion of inequality will be the largest obstacle to sustainable development. Public authorities around the world are strongly recommended to focus on domestic and international measures to resolve inequality, making sustained efforts to design and carry out these measures.

今年1月,新冠疫情突然而至。为了防止疫情扩散,我国采取了史无前例的交通阻断及人流限制措施,这也为我国农业农村经济发展带来了巨大挑战。