A little over two years ago the world shut down as COVID-19 rocked daily activity. The global economy dramatically contracted, but in the Euro Area (EA) and United States (US), the recovery has in many ways exceeded expectations. Both provided more support to workers than in recent recessions, but their approaches differed. Most EA countries relied on furlough schemes that kept workers attached to their employers and paid them not to work, while the US government gave direct income support through expanded unemployment insurance (UI) and stimulus checks. Two years later it is clear each approach had its pros and cons. As economic policymakers gather for the IMF and World Bank Spring Meetings, they should further study this episode and examine their country's fiscal policy infrastructure to ensure both approaches can be efficiently utilized during a future crisis if needed.

At the time of the first COVID-19 lockdowns there was fear in many economies of another Great Depression. However, for large parts of the world, the economic recovery has been stronger and faster than anticipated despite challenges from high inflation and, more recently, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and its economic fallout. For example, at the start of 2022 the EA and US GDP trajectories were already approaching pre-pandemic trend levels. The recovery has been better than past ones in part due to enormous fiscal spending. Compared to the Great Recession, both the EA and US used fiscal stimulus to a much larger degree.

While both the EA and US spent more this time around, how they went about fiscal stimulus was notably different. In the EA, much of the income support for workers was funneled through their employers. Most EA countries paid employers to keep furloughed workers on their payroll while not working, and paid them a high but less than equal percentage of their working wages (on average ~75 percent). In the US, UI was expanded to include more types of workers than previously accepted, the length of time workers could be on UI was extended, and the amount of income support provided was greatly elevated. In some cases, US workers were receiving more than 100 percent of their working income. In addition, multiple rounds of stimulus checks were sent to US households.

Structural differences in EA and US labor markets, differences in spending magnitude, and differences in public health management make policy impact comparisons inexact. However, it is clear both policy regimes were effective and present tradeoffs.

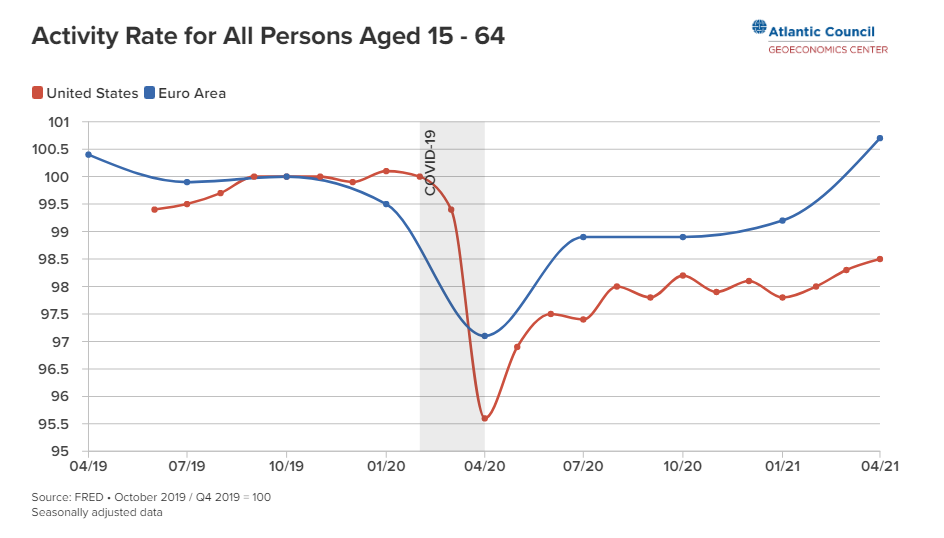

As a result of EA furlough programs, employment levels were affected very little, and much less than in the US. Employment is also back to pre-pandemic levels, unlike in the US. Relatedly, these policies were very successful at keeping workers in the labor force. In many EA countries the labor force participation rate has been higher for most of the pandemic recovery than the US'. Labor market stability is one reason inflation in the EA has been lower than in the US.

On the flip side, real wages for US workers grew faster for much of the recovery because they have been less attached to pre-pandemic employers (though recently both have been struggling with surging inflation). Job switching and competition for labor are driving forces behind rising wages as employers try to attract employees. In addition, self-employed workers likely fared better in the US from direct income support. Lastly, unlike the EA there has been a burst of new business formation in the US, which could have long-run impacts as economies evolve after the pandemic.

From a public finance perspective, it appears the EA was more efficient than the US as the EA has had higher GDP growth per unit of public debt issued. This reflects political choices in terms of how much to spend, policy effectiveness, and differences in administrative capabilities. For example, the US struggled to effectively implement enhanced UI. As a result, a crude measure emerged where one dollar amount was instituted instead of a given percentage level of lost wage income. This led to a larger percentage of Americans receiving more money from UI than they did while working than policymakers necessarily intended. Other areas of inefficiency in the US fiscal response include employee-retention tax credit processing and the primary attempt at a large-scale furlough style policy, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). PPP had positive impacts but also helped lots of employers that likely did not need assistance.

The EA and US fiscal policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have led to stronger economic recoveries than many imagined. However, there is always room for improvement and lessons to be learned. Moving forward EA and US policymakers should assess the strengths and weaknesses of both approaches while improving components of their respective fiscal policy apparatuses as needed. Both furloughed job and income support methods may be needed when responding to future crises. Policymakers should have a complete toolkit available to respond in the most effective and efficient manner.

今年1月,新冠疫情突然而至。为了防止疫情扩散,我国采取了史无前例的交通阻断及人流限制措施,这也为我国农业农村经济发展带来了巨大挑战。