Providing sustainable nutritious foods for the world's population without damaging the environment is the biggest challenge of the 21st century. A growing hungry population across the globe demands increased utilisation of agricultural land, more grazing land for livestock, and more utilisation of fertilizers and genetically modified crops, which would hurt the environment by increased greenhouse gas emissions (GHGe), environment pollution, compromising biodiversity, amongst other consequences. Addressing climate change and ensuring nutritious food for all are our top priorities to save the planet and ourselves.

Food security is based on four dimensions—availability of food, physical and economic accessibility, utilisation and bioavailability, and sustenance of these three dimensions. More than a billion people rely on the current food system for their livelihoods. To meet growing nutritional needs, food production per capita has increased by over 30 percent since 1961, accompanied by an 800 percent rise in utilising nitrogen fertilizers and a 100 percent rise in using water resources for irrigation. Nonetheless, 821 million people are currently undernourished, 151 million children under five are stunted, 613 million women and girls aged 15 to 49 are iron deficient, and 2 billion adults are overweight or obese.

Food production systems and eating habits are major contributors to climate change, and it is impossible to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement unless a radical shift occurs. Eating more plant-based foods will reduce our carbon footprint in no uncertain terms. However, considering the complexity of personalised dietary habits, the transition is not so easy to accomplish. Not everyone can make the switch. In addition, going vegan won't ensure sustainable eating without hurting the environment since GHGe occur at every step of the food production process, including cultivation, harvesting, storing, transporting, and cooking.

The environmental impact of agriculture, food system, and the modern diet

According to the United Nations (UN), food, energy, and water are the three pillars of sustainable development. The increasing world population has led to exponential growth in demand for all three. More than a quarter (26%) of global greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to food. Agriculture uses (Fig. 1) half of all the habitable, including ice-free and desert-free, land in the world, 70% of the world's freshwater and is responsible for 78% of global eutrophication i.e., pollution of waterways with nutrient-rich pollutants.

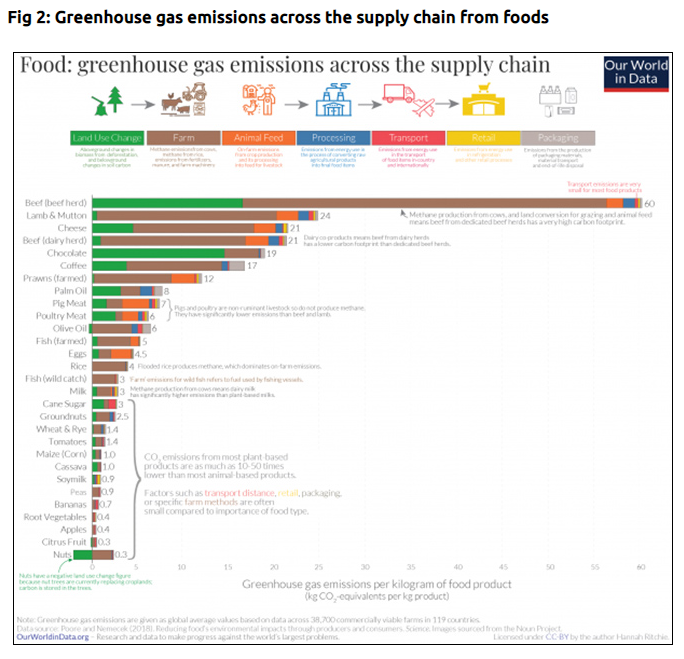

In 2018, a study by the University of Oxford evaluated data from around 38,000 farms across 119 countries and reported that the agricultural process, including transportation and deforestation, led to the production of 13.7 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. which is equivalent to 26% of the GHGe each year. This report also revealed that the production of meat, fish, eggs and dairy occupies 83% of the world's farmland and contribute to 56-58% of GHGe. A visualisation of this report is illustrated in figure 2 depicting GHGe from 29 foods – beef being the top contributor in the list and nuts the least.

Although most GHGe is contributed by animal foods, however, some experts suggest that eliminating meat alone cannot produce a significant impact. According to Jennie I MacDiarmid, a British public health nutritionist, a healthy diet does not necessarily reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and even combining unhealthy foods can reduce their impact on the environment. In a 2021 review, dietitian Sara Forbes reported, 67-73% of Australia's greenhouse gas emission is contributed by the country's core foods, namely, fruit and vegetables, grains, lean meats, fish, eggs, nuts, seeds, beans, legumes, milk and other dairy products. The remaining 27-33% is contributed by non-core or "discretionary" foods like sugary beverages, alcohol, cake, pastries, and processed meats. So, blaming meat consumption alone for environmental damage is scientifically premature.

At the same time, increased production and consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) have also been found to be linked with higher greenhouse gas emission, reported a study published in The Lancet Planetary Health that tracked dietary changes for 30 years. This study from Brazil found that over 30 years of a dietary shift from home-based foods to UPFs has led to a 21% increase in GHGe, a 22% increased contribution to the country's water footprint, and a 17% increased contribution to the ecological footprint. The study mentioned that multiple UPFs contain palm and soy oils that have significant health and environment effects. Additionally, to reduce the impact of animal products on the environment, plant-based, fake meats are becoming increasingly popular that are more environment friendly than animal meat. Nevertheless, some plant-based substitutes, such as those derived from soybeans, are not eco-friendly. Hexane is an air pollutant and potential neurotoxin used in the industrial processing of soybean oil. In addition, soybeans are often genetically modified (GM), and research has shown that these crops use more herbicides and negatively impact the agricultural ecosystem.

A sustainable food system is health-promotive and environment-friendly

Globally, malnutrition and unhealthy diets are among the top 10 risk factors contributing to disease burden. Addressing climate change with a sustainable diet includes strategies to combat all forms of malnutrition including undernutrition, hidden hunger or micronutrient deficiency; and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, diabetes type 2, cardiovascular diseases, amongst others. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United States (FAO), sustainable eating involves consuming foods that have little environmental impact or low carbon footprint but are, at the same time, enriched in essential nutrients to fulfill nutritional needs. Sustainable eating is accessible, economic, diverse, nutritionally adequate, safe, healthy, and culturally acceptable as described by FAO. A section of the world's population is moving towards eating more a plant-based diet to reduce their dietary footprint but going vegan or vegetarian is not an option available to everyone; plant-based foods are not always affordable, and are hard to sustain. Additionally, meatless or vegetarian UPFs laden with refined carbs and trans-fat are unsustainable for both our health and the environment. The following measures are enumerated as part of sustainable eating that will address climate change at the same time.

Eat local – Choose seasonal, local, fresh, home-grown foods. A smaller carbon footprint is created by eating locally by reducing food miles and transportation GHG emissions. For example, breast milk has zero carbon food print compared to artificial formula feeds. A study from 2020 determined that the North American per capita emissions for infants and toddlers from birth to 36 months of age in 2016 were, at the very least, 59.06 kg CO2 equivalent. Promoting breast milk feeding, thus, could be one of the smartest ways to address climate change and childhood malnutrition simultaneously. According to a 2005 report from Toronto, local produce from a farmers’ market travels an average of 101 km to reach the consumer, while imported produce travels an average of 5,364 km. Compared to the basket of local products, imports contributed 11,886.867 grams of CO2 emissions, 100 times more than the basket of local products.

Gradual shift from red meat – Reducing consumption of red meats and switch to white meat and fish such as chicken, turkey, seafood and shellfish is a sustainable way for many. A 2019 review led by Diego Rose and colleagues assessed 16,800 diets and revealed that a beef-based diet had 52% impact on the environment while a shellfish-based diet had just 10% impact. We can, therefore, reduce our carbon footprint by making even small environmentally-conscious food choices without compromising the quality of the diet.

Choose climate-smart crops – Apart from making a shift in choosing meats, it's important to choose climate-smart crops such as millets to reduce carbon footprint and ensure sustainable eating. The year 2023 has been proclaimed the International Year of Millets by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation to make people aware of the health benefits of millets, their sustainability under harsh climate conditions, and their potential as a "future food" in the context of rapid climate change. Millets such as jawar, bajra, ragi, and barley grow well across the globe; require little crop maintenance; and are gluten-free, rich in protein, dietary fiber, and essential micronutrients – iron, calcium, magnesium, B vitamins, etc. These whole grains hold the potential to address the triple burden of malnutrition by reducing micronutrients deficiency, preventing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and obesity, and lowering the risk of undernutrition. A 2018 comparative study from India reported that replacing rice cultivation with maize, finger millet, pearl millet, or sorghum reduced irrigation water demand by 33%.

To sum up – The factors that influence eating habits go beyond health and environmental concerns, such as local availability, seasonality, affordability, and preferences. Shifting to foods with zero or minimum carbon footprint is the best course of action to address climate change. Complete elimination of any food group from the daily diet is impractical and short-lived. The key to an environment-friendly sustainable diet is growing your own food when you can; choosing nutritious whole foods; reducing the consumption of refined carbohydrates, trans-fats, and ultra-processed foods; buying from local vendors; minimising waste; and eating more plant-based foods.

今年1月,新冠疫情突然而至。为了防止疫情扩散,我国采取了史无前例的交通阻断及人流限制措施,这也为我国农业农村经济发展带来了巨大挑战。