Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows fell by 35 per cent in 2020 to $1 trillion, from $1.5 trillion in 2019 (World Investment Report 2021). This is the lowest level since 2005. The pandemic has hit hardest developed economies (-58%) while developing countries proved relatively more resilient (-8%). Yet, a decline in announced greenfield projects and international project finance deals in developing countries is a major concern – with numbers down by 40% and 14% respectively. Both are crucial for improving productive capacity and infrastructure for a sustainable recovery.

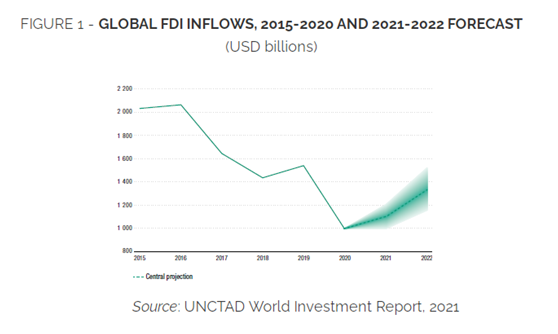

Looking ahead, global FDI flows are expected to bottom out in 2021 and recover some lost ground with an increase of 10% to 15% (Figure 1). This would still leave FDI some 25% below the 2019 level. Current forecasts show a further increase in 2022 which, at the upper bound of projections, bring FDI back to the 2019 level. Prospects are highly uncertain and will depend on, among other factors, the pace of economic recovery and the possibility of pandemic relapses, and the potential impact of recovery spending packages on FDI.

More intraregional investment on the horizon?

The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic arrives on top of existing challenges to the system of international production arising from automation and digitalization, growing economic nationalism, and the sustainability imperative. These structural trends support a shift of international production and FDI towards more regional value chains (World Investment Report 2020).

In 2019 the total value of investment links (FDI stock) between countries in the same geographic region amounted to around $18 trillion USD corresponding to 47% of the total FDI stock ($38 trillion). In other words, on average, one out of two dollars in outstanding foreign investment is between regional partners.

While these data show that intraregional investment is already an important component of global FDI, is there more to this story? Novel empirical analysis conducted by UNCTAD sheds new light on the current status of intraregional FDI, suggesting that progress in regionalism is not as advanced as it may seem from naively looking at the global average.

Uneven regional integration. A global average of intraregional FDI at almost 50% disguises massive differences between regions, with regional integration in the poorest regions, Africa and Latin America and Caribbean, still at a nascent stage (Figure 2). Of USD 18 trillion of intraregional FDI globally, 70% or USD 12.5 trillion are in Europe, USD 4 trillion in Asia and USD 1 trillion in North America. The other regions together (Africa, Latin America and Caribbean, Oceania and South-East Europe and CIS) do not reach 1 USD trillion of intraregional FDI. Differences are not only driven by the size of the regions. The share of intraregional FDI in total FDI stock to the regions ranges from 67% in Europe, to 12% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 10% in Africa. Among developing regions, Asia is by far the most integrated with intraregional FDI covering half of investment stock in the region.

2. Growing slowly. Growth in the regional FDI stock is slower – not faster – than growth in the world FDI stock. In other words, the global economy is not (yet) becoming more regional. The intraregional FDI stock has been growing at 4% annually in the last 10 years while the total FDI stock grew at 6%. As a consequence, the regional share of total FDI dropped by almost 10 percentage points in ten years, from 56% in 2009 to 47% in 2019. The shift towards regional FDI would imply a reversal of the existing trend towards more globalized FDI.

3. Ownership: global rather than regional. More subtly, not all components of intraregional FDI equally contribute to regional economic integration. Links in which both the ultimate owner and the investment are located within the region are arguably more relevant than "artificial" intraregional investment links created by investors from outside the region choosing to channel their investment in the region through a regional hub, where they might locate a holding company, regional headquarters or back-office functions. "Looking through" such regional investment hubs and only counting links between an ultimate investor (owner) and a final destination (of the productive asset) in the same region, the total falls from USD 18 trillion to USD 11 trillion. While the latter number (USD 11 trillion) captures "deep" integration between the sources and destinations of FDI financing, the remaining part (USD 7 trillion or 40% of total intraregional FDI) mainly reflects the role of regional investment hubs as regional conduits and gateways, "tying together" regional FDI networks.

This suggests that while Multi National Enterprises (MNEs) have regionalized to some extent their operational and financial networks, ownership remains substantially global. Between a model of regionalism led by global MNEs diversifying their operations at the regional level and the other led by regional MNEs structuring their operations near-shore, the former has been prevailing so far. In the future this trend may change. Reshoring by global MNEs as a response to policy pressures for regional strategic autonomy, business resilience considerations and the public push for sustainability, may lead to a partial realignment between ownership and operations in developed regions. In parallel, in developing regions, the narrowing of the North-South offshore channel may lead to an intensification of indigenous efforts and initiatives to create regional MNEs and value chains.

Is it about time for regional investment?

Momentum for regional FDI is thus expected to grow further in the wake of the pandemic, in tandem with wider structural transformations already taking in place in the global production system. Policy pressures for regional strategic autonomy, business resilience considerations, and the public push for sustainability are likely to shift investment towards regional production, boosting GVCs within regions. However, our empirical analysis shows that challenges on the way to a broad and inclusive regional integration are significant:

The process of regional integration must primarily address massive divide between Africa and Latin America and Caribbean on the one side and developed regions and Asia on the other.

A substantial acceleration of intra-regional FDI would represent a trend reversal, as over the last decade intra-regional FDI has not kept pace with growth of total FDI.

Any trend towards regionalism in cross-border ownership and production networks (i.e. excluding the conduit role of regional investment hubs) will start from a smaller base than generally thought and may take a longer time than expected

今年1月,新冠疫情突然而至。为了防止疫情扩散,我国采取了史无前例的交通阻断及人流限制措施,这也为我国农业农村经济发展带来了巨大挑战。